Friday 21 February 2020 | Open Table

RITUAL

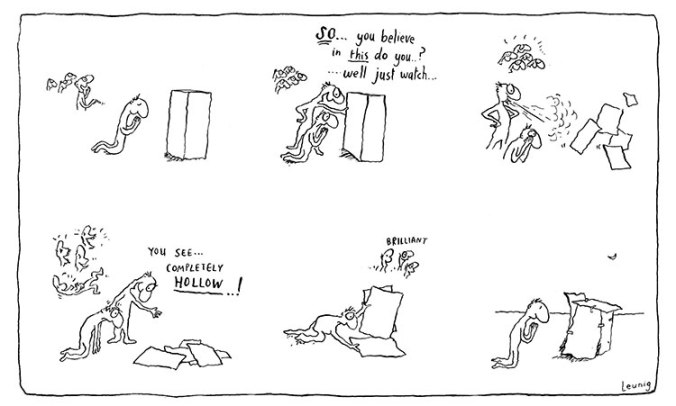

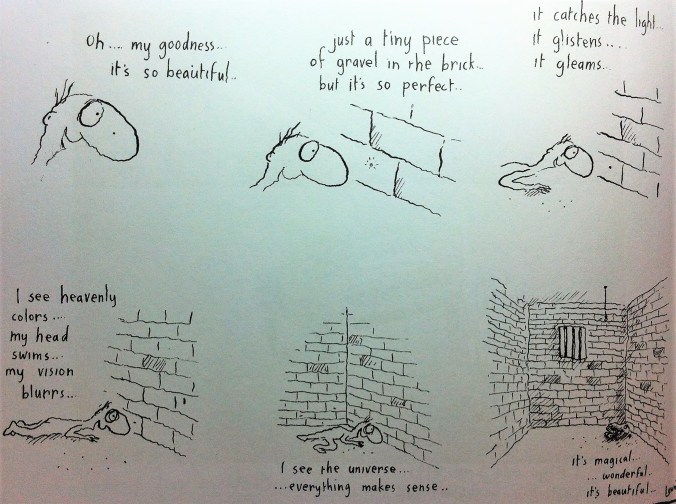

Needled by Michael Leunig’s cartoon “So You Believe in This?” and imaginatively entering the multilayered drama of Exodus 12:1-13:16 (the Passover; echoed in Luke 22:7-20 with Jesus’ Last Supper), we launch Open Table 2020 with a night sharing stories on the theme of RITUAL.

In a culture fixated with the here and now of this immanent frame, any kind of ‘ceremony’ seems suspect and superstitious–empty and easy to knock down. And yet, these richly symbolic and habitual practices tie us into a greater story and a deeper identity–a kind of tactile memory hook re-narrating who we are and what we’re called to do. SO, what rituals are most meaningful to you? What’s involved, how does it work, and to what hope does it point? And how might we discern between living sacrament and stale liturgy?

This exploration leads well into our first Open Book series, dialoguing with Eastern Orthodox scholar-priest Alexander Schmemann, considering his sacramental theology in the classic, For the Life of the World.

Join us, 7:00pm for a 7:30pm start, at Nik and Dave Benson’s place, 152 Tanderra Way, Karana Downs, with bring-your-own pot-luck mains to share (dessert provided), and beautiful conversation in community to follow this graced meal. All are welcome (invite away!), whatever your identity, practice, creed and belief, or lack thereof. Any questions before the night? Call/txt Dave on 0491138487.

Art/Poem | Michael Leunig, “So You Believe in This?”

Text & Reflection | Exodus 12:1-13:16 (Passover Ritual) esp. 12:21-27, and 13:9-10, 16, as a precursor to Luke 22:7-20 (echoed in the Last Supper/Messianic Passover, itself foreshadowing the greater deliverance through Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross):

Moses said, “When you enter the land the Lord has promised to give you, you will continue to observe this ritual. Then your children will ask, ‘What does this ceremony mean?’ And you will reply, ‘It is the Passover sacrifice to the Lord, for he passed over the houses of the Israelites in Egypt. And though he struck the Egyptians, he spared our families.’ … This annual festival will be a visible sign to you, like a mark branded on your hand or your forehead. Let it remind you always to recite this teaching of the Lord: ‘With a strong hand, the Lord rescued you from Egypt.’ So observe the decree of this festival at the appointed time each year.” (Ex 12:21-27, 13:9-10, 16)

Now the Festival of Unleavened Bread arrived, when the Passover lamb is sacrificed. … Jesus took some bread and gave thanks to God for it. Then he broke it in pieces and gave it to the disciples, saying, “This is my body, which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” After supper he took another cup of wine and said, “This cup is the new covenant between God and his people—an agreement confirmed with my blood, which is poured out as a sacrifice for you.” (Luke 22:7-20)

Further thoughts to prime your narrative pump …

Recently we attended some friends’ citizenship ceremony, as they were naturalised as Aussies. I must confess, I was caught out by how similar this service was to an evangelical ‘come to Jesus’ rally.

We stood for the entering of the flags; we sang our national anthem full of antiquated words like ‘girt’; a sermon was delivered by a (Government) Minister decked out in robes, honoring Australian heroes like the ANZACs, and retelling stories of what it means to be called to this promised land; a creed was recited and the penitent stood to acknowledge their serious commitment. “Remember, when you stand and say the pledge, this is the moment when you become a citizen.” For the denoument, the converts walk across the stage to receive their certificate–all set to rapturous applause as these foreigners became part of our extended family–even as this official document was merely the outward sign of an invisible grace that transformation had truly taken place. Afterward we ate a sacred meal of lamingtons and vegemite-smeared bread rolls while sipping lemon tea, all heading back to our homes reminded of our shared identity that binds disparate individuals in a modern democracy.

This elaborate event functioned as a sacrament of sorts. When looking for a picture to accompany the preceding prose, I came across a book by scholar Bridget Byrne (2014), the title of which captured it perfectly: Making Citizens: Public Rituals and Personal Journeys to Citizenship (from the Palgrave “Politics of Identity and Citizenship” Series). So, what am I to make of such a ‘religious’ event in this 21st century ‘secular’ western society? Haven’t we moved past all this clap-trap?

There is something in the post-Christendom mind–even present in pastors and theological educators like me–that is prone to scoff at such symbolic action. It can seem so contrived, artificial, put-on, even pathetic. “So, you believe in this?” Can’t we just talk about these ordinances rather than going through the motions; why not simply agree that it’s merely a mental game, and move on?

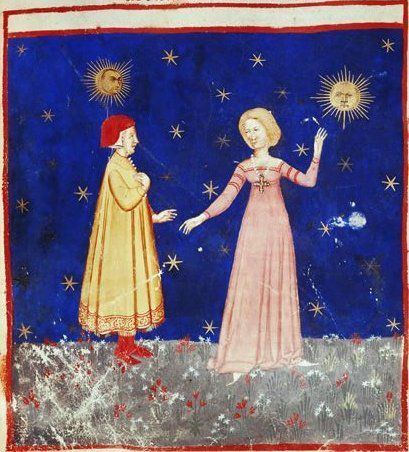

Worse, to the uninitiated, it seems like a gateway to dangerous jingoism, religious fanaticism, and perhaps even distorted occultic fascination among the growing ranks of the ‘spiritual but not religious’. I’m reminded that some of my Protestant forebears had the same attitude shortly after the Reformation to their Catholic brethren, for whom the Communion ritual remains so dear as the place the veil is removed and heaven comes to earth, as captured in this seven minute film.

Juxtaposed with this reverence above, picture the Monty Python Life of Brian scene, when the intelligentsia mishear our Lord’s sermon on the mount to promise that “Blessed are the cheesemakers”–they guffaw, “what’s so special about the cheesemakers?”

Juxtaposed with this reverence above, picture the Monty Python Life of Brian scene, when the intelligentsia mishear our Lord’s sermon on the mount to promise that “Blessed are the cheesemakers”–they guffaw, “what’s so special about the cheesemakers?”

Well, overhearing the Eucharist in Latin, “hoc est corpus“–“this is the body of Christ”–and observing that with the ringing of a common bell the bread apparently transubstantiated into the sacred body of Christ, the Protestant intelligentsia (foreshadowing postmodern deconstructionists) guffawed,

“Hocus pocus! What’s so special about the bread and winemakers?”

We wonder out loud, how is this different to a magic trick, a meaningless ritual best left in the dark ages? Pagan cultus and religious superstition apparently collide, both readily dismissed as pure ignorance in an enlightened era.

We wonder out loud, how is this different to a magic trick, a meaningless ritual best left in the dark ages? Pagan cultus and religious superstition apparently collide, both readily dismissed as pure ignorance in an enlightened era.

And yet, sometimes growing up as individuals and as a culture means entering, in philosopher Paul Ricoeur’s beautiful phrase, a “second naïveté” where these rituals take on fresh meaning, even in an age allergic to religion and far from amused by metaphysics. It’s no virtue, intellectual or ethical, to be so literally minded that we conflate the symbol and its referent, thereby dismissing both as an illusion. Like the Roman general, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, conquering Jerusalem and entering the Holy of Holies in the Temple, to declare it “empty“, perhaps we are all too quick to mock a fundamental aspect of what it means to be human, thus avoiding the divine who takes on flesh to accommodate his presence to our senses, in place of a crass and localised idol.

And yet, sometimes growing up as individuals and as a culture means entering, in philosopher Paul Ricoeur’s beautiful phrase, a “second naïveté” where these rituals take on fresh meaning, even in an age allergic to religion and far from amused by metaphysics. It’s no virtue, intellectual or ethical, to be so literally minded that we conflate the symbol and its referent, thereby dismissing both as an illusion. Like the Roman general, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, conquering Jerusalem and entering the Holy of Holies in the Temple, to declare it “empty“, perhaps we are all too quick to mock a fundamental aspect of what it means to be human, thus avoiding the divine who takes on flesh to accommodate his presence to our senses, in place of a crass and localised idol.

Perhaps we can get at the human aspect of ritual through the great Rafael Nadal, consummate tennis great and man of many habits. To be sure, his rearranging of water bottles, stepping across the line leading with his right foot, and repetitive pick of his pants before serving another ace, looks very quirky to the uninitiated. And yet, our performance as human beings is premised on stringing together numerous routines and habits–collectively comprising rituals–hard-wired through our bodies into neural pathways that gear us up for whatever comes next.

Perhaps we can get at the human aspect of ritual through the great Rafael Nadal, consummate tennis great and man of many habits. To be sure, his rearranging of water bottles, stepping across the line leading with his right foot, and repetitive pick of his pants before serving another ace, looks very quirky to the uninitiated. And yet, our performance as human beings is premised on stringing together numerous routines and habits–collectively comprising rituals–hard-wired through our bodies into neural pathways that gear us up for whatever comes next.

This is how we learn, how we grow, and how the human animal fairly short on instincts is able to accommodate so many foreign environments and thrive. It’s a fine line between superstition and sport-stars having a rich pattern that ties them into a stronger psychological game, reminding them of where they’ve come from, who they presently are, and where they’re going. Again, this is a fundamentally human activity, not a peculiar predilection of ‘religious’ people. (Though, Paul Tillich would argue that to be human is to be religious, in the sense of religare–bound together like ligaments by our ultimate concerns and liturgies to keep what matters most at the centre.)

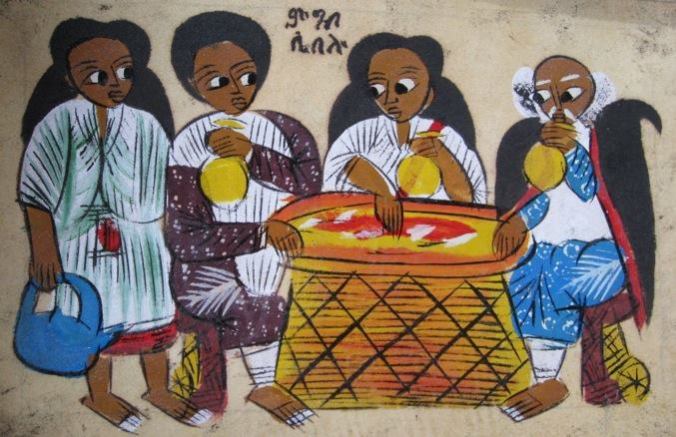

Anthropologists assure us that every culture across time draws on ritual: “a religious or solemn ceremony consisting of a series of actions performed according to a prescribed order.” Whether it’s for birth or death, coming-of-age or getting hitched, work or worship, we draw on rich symbolism and repetitive actions to form new habits that enshrine a particular identity and trace the contours of the cosmos.

Anthropologists assure us that every culture across time draws on ritual: “a religious or solemn ceremony consisting of a series of actions performed according to a prescribed order.” Whether it’s for birth or death, coming-of-age or getting hitched, work or worship, we draw on rich symbolism and repetitive actions to form new habits that enshrine a particular identity and trace the contours of the cosmos.

Jamie Smith captures this well in his “cultural liturgies” trilogy, which we explored in one of our first Open Book series:

Human persons are intentional creatures whose fundamental way of “intending” the world is love or desire. This love or desire—which is unconscious or noncognitive—is always aimed at some vision of the good life, some particular articulation of the kingdom. What primes us to be so oriented—and act accordingly—is a set of habits or dispositions that are formed in us through affective, bodily means, especially bodily practices, routines, or rituals that grab hold of our hearts through our imagination, which is closely linked to our bodily senses. [Desiring the Kingdom, pp62-63. Or for the hoi poloi readable version, see You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit]

True, this is pivotal for religious people gathered together as the church. We are called to be a foretaste of when God sets the world right; we are a sacrament for the life of the world, extended through our practice of multi-sensory rituals such as communion and baptism, embedded in the ongoing story of redemption tracing back to Passover and walking through the Jordan into the promised land. Our past identity and future vision of hope directs our rehearsing—for truth, justice, beauty, and healing—in the present. Ceremony is central to it all, orbiting around God-become-man in the Christ, and climaxing with the bloody cross.

True, this is pivotal for religious people gathered together as the church. We are called to be a foretaste of when God sets the world right; we are a sacrament for the life of the world, extended through our practice of multi-sensory rituals such as communion and baptism, embedded in the ongoing story of redemption tracing back to Passover and walking through the Jordan into the promised land. Our past identity and future vision of hope directs our rehearsing—for truth, justice, beauty, and healing—in the present. Ceremony is central to it all, orbiting around God-become-man in the Christ, and climaxing with the bloody cross.

But, there is a growing recognition among the non-religious–both spiritual and secular alike–that our ephemeral age has not ceased to be human, needing richer liturgies to remind us of who we are, and empower our actions in the search for justice. “Beautiful Trouble“, for instance, is a disparate band of activists seeking a more just world. There’s hardly a Christian among them, but they advocate for leveraging “the power of ritual” to add meaning to their protests–symbolic action capturing what it’s all about.

But, there is a growing recognition among the non-religious–both spiritual and secular alike–that our ephemeral age has not ceased to be human, needing richer liturgies to remind us of who we are, and empower our actions in the search for justice. “Beautiful Trouble“, for instance, is a disparate band of activists seeking a more just world. There’s hardly a Christian among them, but they advocate for leveraging “the power of ritual” to add meaning to their protests–symbolic action capturing what it’s all about.

Bringing these meandering thoughts to a close, “practices are not passe.” We should be cautious before rubbishing ritual. Even as we are right to deconstruct empty man-made customs where any repetitive action is believed to automatically achieve some transcendent result, we are wrong to seek a purely intellectual way in the world, where words alone (sola verbum) empty life of symbol and sacrament. There is a deeper magic in the ways of God, where re-membering the mystery of Christ’s blood shed may be the only balm for a hopeless generation bent on cutting words of shame into their skin. Not merely a memory trick, God is pleased through our everyday motions and the material stuff of bread and wine to redeem and form those who humbly trust this intervention. As we grow up to better grapple with the shape of the universe, let us not be offended that the Creator was pleased to make humanity from the humus of the earth, and draw us into the divine life through such fragile rituals that speak poetically of greater things, embodying the good and directing our gaze upward to the source of grace.

Bringing these meandering thoughts to a close, “practices are not passe.” We should be cautious before rubbishing ritual. Even as we are right to deconstruct empty man-made customs where any repetitive action is believed to automatically achieve some transcendent result, we are wrong to seek a purely intellectual way in the world, where words alone (sola verbum) empty life of symbol and sacrament. There is a deeper magic in the ways of God, where re-membering the mystery of Christ’s blood shed may be the only balm for a hopeless generation bent on cutting words of shame into their skin. Not merely a memory trick, God is pleased through our everyday motions and the material stuff of bread and wine to redeem and form those who humbly trust this intervention. As we grow up to better grapple with the shape of the universe, let us not be offended that the Creator was pleased to make humanity from the humus of the earth, and draw us into the divine life through such fragile rituals that speak poetically of greater things, embodying the good and directing our gaze upward to the source of grace.

+++

Christ’s Pieces pillar, Noel Payne, is the driving force behind this series. He first discovered this book,

Christ’s Pieces pillar, Noel Payne, is the driving force behind this series. He first discovered this book,  As we journey through this series, you may find the following sites and sources helpful to deepen your understanding:

As we journey through this series, you may find the following sites and sources helpful to deepen your understanding:

September 12 | TL II,

September 12 | TL II,

Sabbath involves four key elements:

Sabbath involves four key elements:

Here’s a bit more on the subject:

Here’s a bit more on the subject:

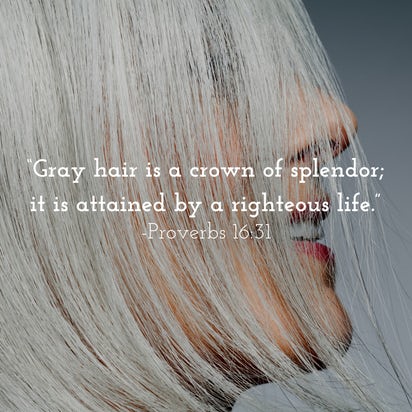

If a “hoary head” isn’t your thing, then perhaps this modern rendering says it best: “Silver hair is a beautiful crown found in a righteous life” (Proverbs 16:31).

If a “hoary head” isn’t your thing, then perhaps this modern rendering says it best: “Silver hair is a beautiful crown found in a righteous life” (Proverbs 16:31).

I’m looking forward to hearing your stories as we gather for this open table. In the spirit of vulnerability and priming the pump, here is a foretaste of what I hope to share, about my favourite ‘wise elder’, who was ‘promoted to glory’ more than a few years ago. It’s a reflection I first wrote as the preface to my Nanna’s poetry collection, later published as a blog on

I’m looking forward to hearing your stories as we gather for this open table. In the spirit of vulnerability and priming the pump, here is a foretaste of what I hope to share, about my favourite ‘wise elder’, who was ‘promoted to glory’ more than a few years ago. It’s a reflection I first wrote as the preface to my Nanna’s poetry collection, later published as a blog on

Recently I was jogging through Noosa National Park with a Canadian friend, pointing out the great diversity and character in the surrounding trees. In place of uniform stands of pines were paperbarks and gnarled gumtrees. Nanna quickly came to mind. Trees like these were features in many of her paintings, and her poems. Nanna loved nature. She used to tell tales of fairies in the garden, replete with intricate details of what each would wear and how they would move. The banksia bush had a larger-than-life personality in her imagination. At the least opportune time—like when picking me up from a friend’s place—Nanna would quietly slip out of the conversation, leaving us all wondering where she’d gone. After looking around, we would find Nanna on her knees, crawling through the garden bed. She was scraping off bits of bark from the base of a gumtree—“It’s for my bark paintings,” she explained. For Nanna, this was normal.

Recently I was jogging through Noosa National Park with a Canadian friend, pointing out the great diversity and character in the surrounding trees. In place of uniform stands of pines were paperbarks and gnarled gumtrees. Nanna quickly came to mind. Trees like these were features in many of her paintings, and her poems. Nanna loved nature. She used to tell tales of fairies in the garden, replete with intricate details of what each would wear and how they would move. The banksia bush had a larger-than-life personality in her imagination. At the least opportune time—like when picking me up from a friend’s place—Nanna would quietly slip out of the conversation, leaving us all wondering where she’d gone. After looking around, we would find Nanna on her knees, crawling through the garden bed. She was scraping off bits of bark from the base of a gumtree—“It’s for my bark paintings,” she explained. For Nanna, this was normal. Perhaps in the title to her final collection of poems we can find the answer: Rainbows in the Tears. For when love looks through tears of pain, a vision of hope will emerge.

Perhaps in the title to her final collection of poems we can find the answer: Rainbows in the Tears. For when love looks through tears of pain, a vision of hope will emerge. Nell was known as a woman of faith. But this was not “faith in faith” or some subjective impulse to trust beyond reason. Not at all. Instead, my Nanna trusted in the one true God, who was able to take the worst suffering, and the greatest injustice, and turn it into new grace and hope for all humanity. At the Bible’s climax we see God Himself in the person of Jesus, left high and dry as He opened His arms to embrace a world gone awry. Love is cruciform. And love is passionate, where passion literally means to “suffer with.” So Nanna had faith in the God with scars. When Nanna looked through tear stained eyes at the resurrected Christ, she knew all her sad stories would one day come untrue. And the result was art fuelled by hope.

Nell was known as a woman of faith. But this was not “faith in faith” or some subjective impulse to trust beyond reason. Not at all. Instead, my Nanna trusted in the one true God, who was able to take the worst suffering, and the greatest injustice, and turn it into new grace and hope for all humanity. At the Bible’s climax we see God Himself in the person of Jesus, left high and dry as He opened His arms to embrace a world gone awry. Love is cruciform. And love is passionate, where passion literally means to “suffer with.” So Nanna had faith in the God with scars. When Nanna looked through tear stained eyes at the resurrected Christ, she knew all her sad stories would one day come untrue. And the result was art fuelled by hope.

+++

+++

“Wanderlust” [

“Wanderlust” [ The desire to move about thus takes on a different hue when we consider mass migration in this era of the refugee. Unprecedented numbers of people are streaming across Europe, and occasionally reaching our shores, out of foreign cultures such as Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, and Syria. While debates rage at “home” about what makes for a refugee as distinct from an “economic migrant”, this is hardly a case of wanderlust. The price paid is immense, to uproot from the known (however decimated it may now be), and set out to a new land without the money and language and networks to make any plans that guarantee safety, let alone a better life. Unsurprisingly, many of these children dream of returning to their homeland, and rebuilding what was to recapture their sense of identity and stability. (Take for instance,

The desire to move about thus takes on a different hue when we consider mass migration in this era of the refugee. Unprecedented numbers of people are streaming across Europe, and occasionally reaching our shores, out of foreign cultures such as Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, and Syria. While debates rage at “home” about what makes for a refugee as distinct from an “economic migrant”, this is hardly a case of wanderlust. The price paid is immense, to uproot from the known (however decimated it may now be), and set out to a new land without the money and language and networks to make any plans that guarantee safety, let alone a better life. Unsurprisingly, many of these children dream of returning to their homeland, and rebuilding what was to recapture their sense of identity and stability. (Take for instance,

As one who loves rock-climbing, snapped his neck in a gymnastics accident, and still commutes on a motorbike most every day, I get this

As one who loves rock-climbing, snapped his neck in a gymnastics accident, and still commutes on a motorbike most every day, I get this  Definitions vary, but pay attention to the valence. Risk has a negative aspect. It’s the possibility of loss or injury: peril; someone or something that creates or suggests a hazard. In other words, risk is the exposure to the likelihood of injury or loss; put simply, it’s a dangerous and chancy choice.

Definitions vary, but pay attention to the valence. Risk has a negative aspect. It’s the possibility of loss or injury: peril; someone or something that creates or suggests a hazard. In other words, risk is the exposure to the likelihood of injury or loss; put simply, it’s a dangerous and chancy choice. It’s no artificial segueway to see that this is now about that. This worldly risk is also about that greater good. As

It’s no artificial segueway to see that this is now about that. This worldly risk is also about that greater good. As  Test case: Creation. The all-sufficient Risk-Taker whose essence is communion, overflowed in the perichoretic dance to creatively birth the cosmos. The motivation was love, and the reward was shalom, weaving us together through right relationship with God, neighbour, self and creation, all pointing back to its transcendent source. The risk is for everyone, not simply God in a zero-sum game; holistic flourishing, like African

Test case: Creation. The all-sufficient Risk-Taker whose essence is communion, overflowed in the perichoretic dance to creatively birth the cosmos. The motivation was love, and the reward was shalom, weaving us together through right relationship with God, neighbour, self and creation, all pointing back to its transcendent source. The risk is for everyone, not simply God in a zero-sum game; holistic flourishing, like African  Like I said, though, Christmas is a time of injury.

Like I said, though, Christmas is a time of injury. The unlimited, all knowing, all powerful Creator, tied himself to matter and was confined to a crib in a baby’s body. God hurt. And forget those romanticised Christmas carols: “meek and mild, no crying he makes”. No, this was first century Palestine, no more peaceful than today (cf.

The unlimited, all knowing, all powerful Creator, tied himself to matter and was confined to a crib in a baby’s body. God hurt. And forget those romanticised Christmas carols: “meek and mild, no crying he makes”. No, this was first century Palestine, no more peaceful than today (cf.  It’s captured well in the iconic Greek Orthodox painting “Slaughter of the Innocents”. Granted, the statistics suffer symbolic inflation over this feast honouring the “

It’s captured well in the iconic Greek Orthodox painting “Slaughter of the Innocents”. Granted, the statistics suffer symbolic inflation over this feast honouring the “ The risk of incarnation led inexorably to the crucifixion, the final relinquishment of divine power, not for personal gain, but that all may be set free from the ultimate demonic despot, finding life in renewed relationship with God, neighbour, planet and self. Literally, this risk offered a sign, a fore-taste, of “

The risk of incarnation led inexorably to the crucifixion, the final relinquishment of divine power, not for personal gain, but that all may be set free from the ultimate demonic despot, finding life in renewed relationship with God, neighbour, planet and self. Literally, this risk offered a sign, a fore-taste, of “ Transposed into the modern world, where facing today’s Herods requires the combined courage of Mary and the Messiah, Chesterton composed this poem:

Transposed into the modern world, where facing today’s Herods requires the combined courage of Mary and the Messiah, Chesterton composed this poem: And the mother still joys for the whispered

And the mother still joys for the whispered Returning, then, to our key theme, and inspired by Parker Palmer’s

Returning, then, to our key theme, and inspired by Parker Palmer’s

In delving into this theme, I discovered a Spotify playlist with 1.5 million followers entitled “The Most Beautiful Songs in the World.” And I stumbled upon “

In delving into this theme, I discovered a Spotify playlist with 1.5 million followers entitled “The Most Beautiful Songs in the World.” And I stumbled upon “ Search “beauty” on

Search “beauty” on

Despite our post-modern penchant for inverting age-old symbols,

Despite our post-modern penchant for inverting age-old symbols,  In this same stunning essay,

In this same stunning essay,

Maybe this is why God went to the trouble of prescribing

Maybe this is why God went to the trouble of prescribing

Bringing this wide-ranging provocation to a close, what story, person, experience or object from your life comes to mind when you think of beauty? When do you typically employ the qualifier, beautiful? And is there any sense in which you believe—or, better yet, have tasted—that your subjective encounter with beauty points to The Beautiful, as the third transcendental, travelling with her sisters, The True and the Good?

Bringing this wide-ranging provocation to a close, what story, person, experience or object from your life comes to mind when you think of beauty? When do you typically employ the qualifier, beautiful? And is there any sense in which you believe—or, better yet, have tasted—that your subjective encounter with beauty points to The Beautiful, as the third transcendental, travelling with her sisters, The True and the Good?

Art | Michael Leunig, “

Art | Michael Leunig, “ When a word can mean everything, it ceases to mean anything. So, what do we mean by “good”? In modern parlance, it’s highly malleable. For ancients, however, it was the second transcendental, alongside truth and beauty. It was the perennial quest for quality.

When a word can mean everything, it ceases to mean anything. So, what do we mean by “good”? In modern parlance, it’s highly malleable. For ancients, however, it was the second transcendental, alongside truth and beauty. It was the perennial quest for quality. And yet, how do we measure excellence? Surely good implies its counterpart bad, and draws on some objective standard by which we judge? Good thus draws us deeper into questions of identity, essence, purpose, destiny/telos … some larger story heading either here or there, in which the part–whether a pizza or a person–rightly relates to the whole.

And yet, how do we measure excellence? Surely good implies its counterpart bad, and draws on some objective standard by which we judge? Good thus draws us deeper into questions of identity, essence, purpose, destiny/telos … some larger story heading either here or there, in which the part–whether a pizza or a person–rightly relates to the whole.