Friday 6 October 2017 | Open Table

on the theme of the third transcendental, THE BEAUTIFUL

Bring a main dish to share, and come with a story to tell in response to the stimulus below, at Nik and Dave Benson’s place, 152 Tanderra Way, Karana Downs, at 7:30pm. Any questions? Call/txt Dave on 0491138487.

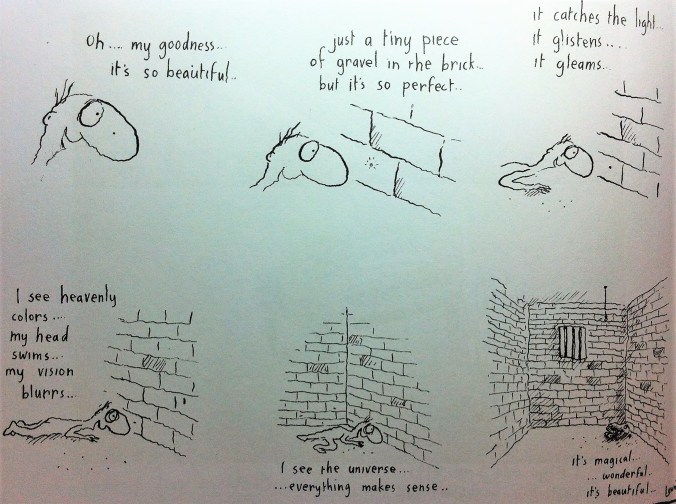

Art | Michael Leunig, Glorious Gravel [My title! Image above]

Text | Exodus 28: 1-5, 31-41 “Clothing for the Priests”

Extra | Plotinus (3rd Century BCE, Greek Philosopher) Enneads I.6 “On Beauty” (4 minute video grab or full text here, especially §3-4,6) OR Hans Urs von Balthasar excerpt on Beauty here.

What does beauty mean to you? And when’s the last time you used the word “beautiful”? As an adjective, it seems capable of qualifying almost anything. A beautiful … sunset, dress, speech, meal, painting, putt, mind, person. The list goes on.

In delving into this theme, I discovered a Spotify playlist with 1.5 million followers entitled “The Most Beautiful Songs in the World.” And I stumbled upon “Euler’s Identity”, voted by physicists as “the most beautiful equation”. If you failed senior maths, this will strike you as bizarre. And yet, this formula is arguably beautiful as it travels together with truth—spirituality and science strangely coinhering—and it takes an exceptionally trained mind to see and appreciate a dance of complexity and elegance representing “some of the most profound rules that govern the Universe and everything in it.” This appreciation often travels together with cultivating a poetic or musical ear to discern acoustic order. For those lacking ears to hear or eyes to see, however, it’s almost impossible to define what makes it a thing of beauty, and ultimately—philosophically and theologically—what beauty means.

In delving into this theme, I discovered a Spotify playlist with 1.5 million followers entitled “The Most Beautiful Songs in the World.” And I stumbled upon “Euler’s Identity”, voted by physicists as “the most beautiful equation”. If you failed senior maths, this will strike you as bizarre. And yet, this formula is arguably beautiful as it travels together with truth—spirituality and science strangely coinhering—and it takes an exceptionally trained mind to see and appreciate a dance of complexity and elegance representing “some of the most profound rules that govern the Universe and everything in it.” This appreciation often travels together with cultivating a poetic or musical ear to discern acoustic order. For those lacking ears to hear or eyes to see, however, it’s almost impossible to define what makes it a thing of beauty, and ultimately—philosophically and theologically—what beauty means.

Simplistically defined, beautiful means “pleasing the senses or mind aesthetically”. Anything or anyone that can elicit this perceptual experience of satisfaction in another is labelled “beautiful”. Sounds like it’s more about the spectator, rather than a quality in the object itself, held to some higher standard. You know, “beauty is in the eye of the beholder”.

Search “beauty” on google images, and you’re bombarded with breezy pictures of young women, often plastered with make-up and typically caucasian. No wonder singers like Christina Aguilera (“You Are Beautiful”) and Marilyn Manson (“The Beautiful People”) deconstruct the stereotypes which have shut our eyes to the diffuse beauty of a thousand flowers blooming in all shapes and sizes—rarely confined to what the market conditions us to consume.

Search “beauty” on google images, and you’re bombarded with breezy pictures of young women, often plastered with make-up and typically caucasian. No wonder singers like Christina Aguilera (“You Are Beautiful”) and Marilyn Manson (“The Beautiful People”) deconstruct the stereotypes which have shut our eyes to the diffuse beauty of a thousand flowers blooming in all shapes and sizes—rarely confined to what the market conditions us to consume.

Besides which, as we learn from stories as disparate as Shallow Hal, Beauty and the Beast, Shrek, and The Picture of Dorion Gray, physical and moral beauty in a broken world rarely travel together. The recently deceased Hugh Hefner may have surrounded himself with stunning Playboy Bunnies, but no one dedicates his eulogy to a beautiful life well lived among paragons of pulchritude. Bottom line: we must be cautious before reducing “beauty” to any one look.

And yet, these caveats fail to dismiss beauty as merely subjective. As Alain de Botton observes in his School of Life video, our language, photography and travel plans reveal amazing overlap in what images and destinations we find attractive; on the grounds of democracy alone, there seems to be something objective to beauty, which we ignore to the detriment of all. Which city needs another ugly concrete skyscraper? Beauty is intended to draw us onward and upward. In Dwayne Huebner’s words, it’s the “lure of the transcendent”.

And yet, these caveats fail to dismiss beauty as merely subjective. As Alain de Botton observes in his School of Life video, our language, photography and travel plans reveal amazing overlap in what images and destinations we find attractive; on the grounds of democracy alone, there seems to be something objective to beauty, which we ignore to the detriment of all. Which city needs another ugly concrete skyscraper? Beauty is intended to draw us onward and upward. In Dwayne Huebner’s words, it’s the “lure of the transcendent”.

Now, you could argue that this allure is simply explained by survival. Humans are like Bower Birds, seeking out beautiful blue objects to adorn our nests, even bodies, drawing a partner to propagate our species. And yet, the sheer excess—even superfluity—and diversity of beauty in our universe overflows such reductionism. Instead, it appears to point beyond itself to something that perhaps truly is “beautiful” in essence … an ideal, or form of sorts—even as I have some theological qualms with neo-Platonism as a Greek philosophy distorting Christianity’s affirmation of the material world as “very good” apart from disembodied ideas.

Despite our post-modern penchant for inverting age-old symbols, Michael Leunig suggests that the best “art … is not entirely of this world. … Perhaps it is a flight into beauty and eternity.” Rightly oriented, it is capable of directing our gaze heavenward, passing through and beyond our mundane material existence.

Despite our post-modern penchant for inverting age-old symbols, Michael Leunig suggests that the best “art … is not entirely of this world. … Perhaps it is a flight into beauty and eternity.” Rightly oriented, it is capable of directing our gaze heavenward, passing through and beyond our mundane material existence.

In the words of C. S. Lewis,

The books or the music in which we thought the beauty was located will betray us if we trust to them; it was not in them, it only came through them, and what came through them was longing. These things—the beauty, the memory of our own past—are good images of what we really desire; but if they are mistaken for the thing itself they turn into dumb idols, breaking the hearts of their worshipers. For they are not the thing itself; they are only the scent of a flower we have not found, the echo of a tune we have not heard, news from a country we have never yet visited.

In this same stunning essay, The Weight of Glory (1942), Lewis notes that beauty and “glory”, biblically framed, do travel together. (Or, in Jonathan Edwards’ theology, like flares from the Sun, we perceive beauty as an emanation from a radiant Triune source.) Far from trite conceptions of becoming “a kind of living electric light bulb”, our human longing for glory makes sense like our human fascination with watching the sunrise. Granted, it’s an imperfect sign. But it’s a faithful pointer to something more. Glory is “brightness, splendour, luminosity.” More than perceiving beauty, stimulating our senses, in a very real way we want “to be united with the beauty we see, to pass into it, to receive it into ourselves, to bathe in it, to become part of it.” And this process quite often passes through pain, being remade, reconstituted even by a reality beyond our control. Collateral Beauty may thus sneak up on us, shining through our darkest times of suffering.

In this same stunning essay, The Weight of Glory (1942), Lewis notes that beauty and “glory”, biblically framed, do travel together. (Or, in Jonathan Edwards’ theology, like flares from the Sun, we perceive beauty as an emanation from a radiant Triune source.) Far from trite conceptions of becoming “a kind of living electric light bulb”, our human longing for glory makes sense like our human fascination with watching the sunrise. Granted, it’s an imperfect sign. But it’s a faithful pointer to something more. Glory is “brightness, splendour, luminosity.” More than perceiving beauty, stimulating our senses, in a very real way we want “to be united with the beauty we see, to pass into it, to receive it into ourselves, to bathe in it, to become part of it.” And this process quite often passes through pain, being remade, reconstituted even by a reality beyond our control. Collateral Beauty may thus sneak up on us, shining through our darkest times of suffering.

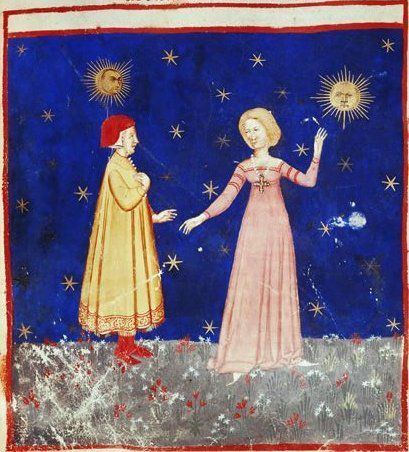

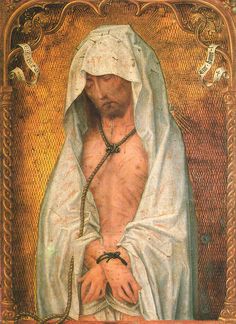

Perhaps this is why we find truly “beautiful souls”—especially those who have emerged through struggle with battle-scars and yet a soft heart—so attractive? They graciously wear the virtues in which we long to be clothed. Thus the Bible persistently refers to putting on “the beauty of holiness” (e.g., Psalms 29:2; 96:9; cf. here), reflecting The Beautiful, being Godself. It takes a radiant character like Beatrice to draw damned Dante out of the Inferno and into Paradise. Similarly, our artwork, our creativity, even our fashion may in a real sense be drawing us to mimic and experience—albeit imperfectly like young girls smearing bright red lipstick on their face, yearning to be like their model mums—a beauty of character that is more than skin deep. We increasingly transform into the likeness of what we admire, imitating what we magnify and that upon which we meditate. In short, we become what we worship.

Perhaps this is why we find truly “beautiful souls”—especially those who have emerged through struggle with battle-scars and yet a soft heart—so attractive? They graciously wear the virtues in which we long to be clothed. Thus the Bible persistently refers to putting on “the beauty of holiness” (e.g., Psalms 29:2; 96:9; cf. here), reflecting The Beautiful, being Godself. It takes a radiant character like Beatrice to draw damned Dante out of the Inferno and into Paradise. Similarly, our artwork, our creativity, even our fashion may in a real sense be drawing us to mimic and experience—albeit imperfectly like young girls smearing bright red lipstick on their face, yearning to be like their model mums—a beauty of character that is more than skin deep. We increasingly transform into the likeness of what we admire, imitating what we magnify and that upon which we meditate. In short, we become what we worship.

Maybe this is why God went to the trouble of prescribing Aaron’s outfit, as Israel’s High Priest, holy and whole in “glorious and beautiful” attire (Exodus 28)? Dressed in holiness we can see God; lacking the gracious covering of divine beauty, we risk being consumed in the encounter.

Maybe this is why God went to the trouble of prescribing Aaron’s outfit, as Israel’s High Priest, holy and whole in “glorious and beautiful” attire (Exodus 28)? Dressed in holiness we can see God; lacking the gracious covering of divine beauty, we risk being consumed in the encounter.

And thus we loop back to our original observation. Beauty can qualify most anything. But, like the 14th Century Italian employment of Botticelli to depict Fortitude, Beauty comes into its own when it illuminates virtue and aligns with the way God intended the world to be, “danc[ing] as an uncontained splendor around the double constellation of the true and the good and their inseparable relation to one another” (von Balthasar).

Not all that glitters is gold, this is true. In the history of empire, circuses and spectacle have been used to deceive and poison the masses, obscuring the really real. “Charm is deceptive, and beauty is fleeting …” (Proverbs 31:30). And yet, gold does have a glitter meaningful in and of itself, pointing beyond to Beauty, perhaps even a transcendent source of unfading glory we call “God”. As the editors of the Kalos (Greek for Beautiful) book series aver,

Not all that glitters is gold, this is true. In the history of empire, circuses and spectacle have been used to deceive and poison the masses, obscuring the really real. “Charm is deceptive, and beauty is fleeting …” (Proverbs 31:30). And yet, gold does have a glitter meaningful in and of itself, pointing beyond to Beauty, perhaps even a transcendent source of unfading glory we call “God”. As the editors of the Kalos (Greek for Beautiful) book series aver,

[the beautiful] is the call of the good; that which arouses interest, desire: “I am here.” Beauty brings the appetite to rest at the same time as it wakens the mind from its daily slumber, calling us to look afresh at that which is before our very eyes. It makes virgins of us all, and of everything—there, before us, lies something that we never noticed before. Beauty consists in integritas sive perfectio [integrity and perfection] and claritas [brightness/clarity]. It is the reason why we rise and why we sleep—that great night of dependence, one that reveals the borrowed existence of all things …. Here lies the ground of all science, of philosophy, and of all theology, indeed of our each and every day.

Bringing this wide-ranging provocation to a close, what story, person, experience or object from your life comes to mind when you think of beauty? When do you typically employ the qualifier, beautiful? And is there any sense in which you believe—or, better yet, have tasted—that your subjective encounter with beauty points to The Beautiful, as the third transcendental, travelling with her sisters, The True and the Good?

Bringing this wide-ranging provocation to a close, what story, person, experience or object from your life comes to mind when you think of beauty? When do you typically employ the qualifier, beautiful? And is there any sense in which you believe—or, better yet, have tasted—that your subjective encounter with beauty points to The Beautiful, as the third transcendental, travelling with her sisters, The True and the Good?

Let the conversation begin!

Art | Michael Leunig, “

Art | Michael Leunig, “ When a word can mean everything, it ceases to mean anything. So, what do we mean by “good”? In modern parlance, it’s highly malleable. For ancients, however, it was the second transcendental, alongside truth and beauty. It was the perennial quest for quality.

When a word can mean everything, it ceases to mean anything. So, what do we mean by “good”? In modern parlance, it’s highly malleable. For ancients, however, it was the second transcendental, alongside truth and beauty. It was the perennial quest for quality. And yet, how do we measure excellence? Surely good implies its counterpart bad, and draws on some objective standard by which we judge? Good thus draws us deeper into questions of identity, essence, purpose, destiny/telos … some larger story heading either here or there, in which the part–whether a pizza or a person–rightly relates to the whole.

And yet, how do we measure excellence? Surely good implies its counterpart bad, and draws on some objective standard by which we judge? Good thus draws us deeper into questions of identity, essence, purpose, destiny/telos … some larger story heading either here or there, in which the part–whether a pizza or a person–rightly relates to the whole.

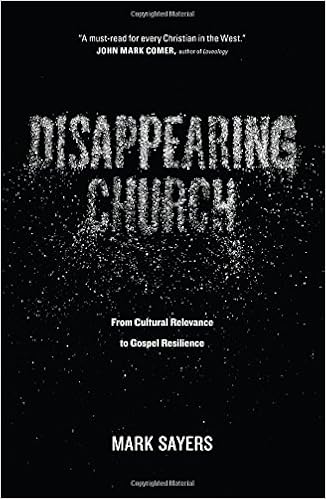

In our second cycle for 2017 (starting Thursday 27th July), we turn to explore the challenge of a community sustaining its faith in a secular culture toxic to deep commitment:

In our second cycle for 2017 (starting Thursday 27th July), we turn to explore the challenge of a community sustaining its faith in a secular culture toxic to deep commitment: Our conversation partner is American conservative and Eastern Orthodox devotee, Rod Dreher. His book,

Our conversation partner is American conservative and Eastern Orthodox devotee, Rod Dreher. His book,  Okay, the tone of these reviews not-so-subtly communicates that I’ve stopped short of the monastic gates to Mr. Dreher’s Benedictine retreat. I’m not particularly conservative, I detest self-concerned protectionism, and this book is far more right-leaning than most of Open Book’s offerings here-to-fore. So, why bother with this diatribe?

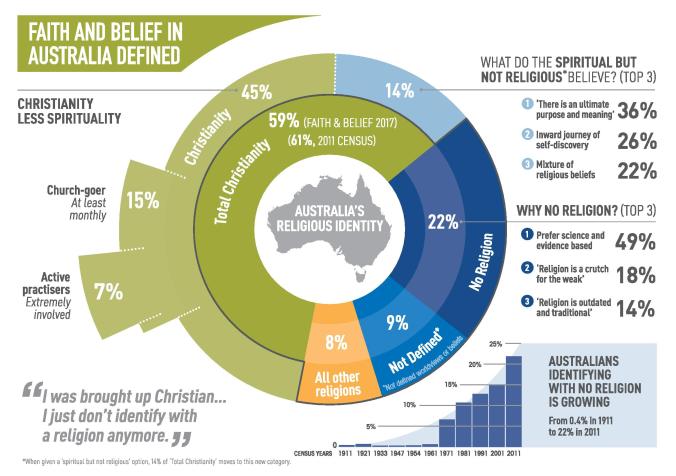

Okay, the tone of these reviews not-so-subtly communicates that I’ve stopped short of the monastic gates to Mr. Dreher’s Benedictine retreat. I’m not particularly conservative, I detest self-concerned protectionism, and this book is far more right-leaning than most of Open Book’s offerings here-to-fore. So, why bother with this diatribe? And for two, it asks questions Aussie Christians must answer. How can we sustain faith in an increasingly secular context—one which corrodes contemporary Christianity faster than an iron ark on a salty sea? Since the Australian Bureau of Statistics released its

And for two, it asks questions Aussie Christians must answer. How can we sustain faith in an increasingly secular context—one which corrodes contemporary Christianity faster than an iron ark on a salty sea? Since the Australian Bureau of Statistics released its  The situation is markedly more dire if you delve below the superficial ABS data, and dive into the 2016 NCLS “

The situation is markedly more dire if you delve below the superficial ABS data, and dive into the 2016 NCLS “ The

The  What is the role of God’s people in an increasingly post-christian West? Are we activist exiles or quaint keepers of an ancient flame? Are we to lean in to culture and insist on our right to act as chaplains to a fading Christendom, or should we withdraw and exercise the ‘Benedict option’? What is a creative and biblical strategy for how the church is to be in a context where God’s people feel increasingly marginalised and overlooked.

What is the role of God’s people in an increasingly post-christian West? Are we activist exiles or quaint keepers of an ancient flame? Are we to lean in to culture and insist on our right to act as chaplains to a fading Christendom, or should we withdraw and exercise the ‘Benedict option’? What is a creative and biblical strategy for how the church is to be in a context where God’s people feel increasingly marginalised and overlooked.

Sure, it’s associated with politics in this

Sure, it’s associated with politics in this

o, what exactly is OPEN TABLE?

o, what exactly is OPEN TABLE? The book is Amy Sherman’s

The book is Amy Sherman’s

Over the last three books, we’ve explored the importance of our bodies and imagination in forming kingdom habits (

Over the last three books, we’ve explored the importance of our bodies and imagination in forming kingdom habits ( Ever since Constantine’s ‘vision’ of the Chi-Rho–‘

Ever since Constantine’s ‘vision’ of the Chi-Rho–‘ Enter Brian Walsh and Sylvia Keesmaat with their provocative commentary,

Enter Brian Walsh and Sylvia Keesmaat with their provocative commentary,

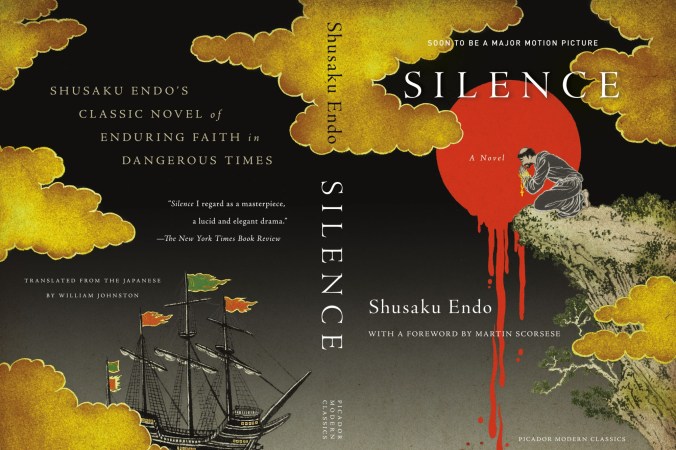

Endō, a Japanese Catholic, was no stranger to occupying the place of the Other: too foreign, too Oriental, to be understood by the West, and too Christian, too iconoclastic–not to mention insufficiently Buddhist–to be accepted at home. His work of historical fiction is set in 1635 as Portuguese missionaries seek to proselytise the Japanese during a time of extreme persecution. Following rumours of their leader (Ferreira) abandoning his faith, two younger Jesuits (Fr. Rodrigues and his companion Fr. Francisco Garrpe) head to Japan to uncover the truth and shore up the struggling converts. How will this collision between cultures resolve, as each grapples with the other? Will Rodrigues and Garrpe, too, betray their Lord, trampling his crudely formed icon (

Endō, a Japanese Catholic, was no stranger to occupying the place of the Other: too foreign, too Oriental, to be understood by the West, and too Christian, too iconoclastic–not to mention insufficiently Buddhist–to be accepted at home. His work of historical fiction is set in 1635 as Portuguese missionaries seek to proselytise the Japanese during a time of extreme persecution. Following rumours of their leader (Ferreira) abandoning his faith, two younger Jesuits (Fr. Rodrigues and his companion Fr. Francisco Garrpe) head to Japan to uncover the truth and shore up the struggling converts. How will this collision between cultures resolve, as each grapples with the other? Will Rodrigues and Garrpe, too, betray their Lord, trampling his crudely formed icon (

We must, however, count the cost. Incarnation always leads to the cross.

We must, however, count the cost. Incarnation always leads to the cross. Recapping this first point, then, our times increasingly resemble the novel’s setting. Christianity, once popular and even powerful, is on the outer, and a nation “come of age” is prone–with some good reason–to marginalise and even persecute the Church as a threat to the common (read “secular”) good. As missiologist Lesslie Newbigin argues powerfully (see

Recapping this first point, then, our times increasingly resemble the novel’s setting. Christianity, once popular and even powerful, is on the outer, and a nation “come of age” is prone–with some good reason–to marginalise and even persecute the Church as a threat to the common (read “secular”) good. As missiologist Lesslie Newbigin argues powerfully (see  Mercifully shorter than my first rationale, a second reason this book is timely to discuss is that the much anticipated movie rendering of Silence by Martin Scorsese has come! Thirty years in gestation since first reading, this master director describes its production as his own “pilgrimage”. It’s set to be released in Brisbane on February 16, 2017. God willing, we’ll watch it together on Thursday March 2. Obviously watching the movie, mid cycle in Open Book, comes with a complete “spoiler alert”! That said, his adaptation is receiving

Mercifully shorter than my first rationale, a second reason this book is timely to discuss is that the much anticipated movie rendering of Silence by Martin Scorsese has come! Thirty years in gestation since first reading, this master director describes its production as his own “pilgrimage”. It’s set to be released in Brisbane on February 16, 2017. God willing, we’ll watch it together on Thursday March 2. Obviously watching the movie, mid cycle in Open Book, comes with a complete “spoiler alert”! That said, his adaptation is receiving